Daphne Caruana Galizia, murdered by a car bomb in Malta in 2017. Jàn Kuciak, shot in the head in Slovakia in 2018. Viktoria Marinova, raped and strangled in Bulgaria. Has Europe become dangerous for journalists? Some areas of Italy always have been, and none more so than Sicily.

The imperilled status of press freedom in Italy has jumped into the spotlight in recent years as stories like that of Roberto Saviano — who has lived under police protection since 2006 for his journalistic work — have gained international attention. But about 200 other reporters in Italy share the same status as Saviano, and many more endure intimidation for their work without ever making headlines.

According to the Council of Europe’s 2019 annual report on media freedom in the EU, Italy is among the countries with the highest number of journalist-safety alerts — the same as the Russian Federation. As mafia clans put down their roots all over Italy, reporting on them often implies getting caught up in a spiral of specious legal complaints and threatening mail, as well as intimidation by politicians and physical threats.

In Sicily, the Italian region with the highest number of reporters killed in mafia or terrorist attacks since 1960, covering corruption or organised crime has long been a daily struggle, especially for local and freelance reporters.

Salvo Palazzolo: “The mafia isn’t just a Sicilian problem.”

On a rainy Tuesday morning in Palermo, Salvo Palazzolo drives up the hills of Passo di Rigano, a neighbourhood on the outskirts of the city famous for being the reign of the Inzerillo mafia family, which he has been investigating for the past few years. Heading out from the island’s capital, the magnificent arabesque buildings of the city centre give way to tower blocks and run-down houses amidst evergreen vegetation.

Palazzolo, 49, is a reporter for the national daily La Repubblica. He started his career at 22, around the time that bomb attacks in Palermo killed Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino, two prosecutors who became symbols of a fight against ruthless criminal clans infiltrating politics and institutions in Sicily and beyond. As a city reporter covering courts and justice, Palazzolo works to uncover the crimes and secrets still gripping Sicily twenty-seven years after those killings. The season of mafia-led mass violence is over, but that doesn’t mean that the mafia has vanished. Its methods have shifted, and reporters like Palazzolo need to account for their renewed international dimension, as manifest in their connections with drug cartels abroad for example.

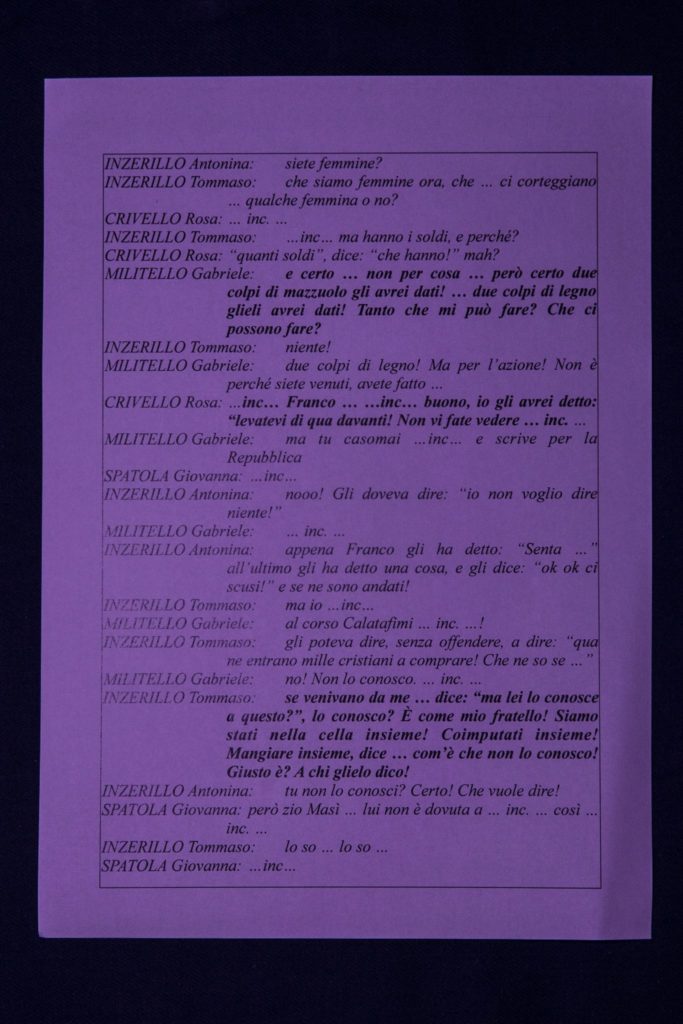

Palazzolo doesn’t hold back a smile, even when talking about his most difficult days. In the summer of 2019, police wiretaps revealed that members of the Inzerillo clan had been talking about physically attacking him after he showed up to ask them some questions at a shop they keep in Passo di Rigano. Earlier that year, a priest who had officiated a service for a deceased mobster told Palazzolo that sooner or later he would pay for his questioning. The year before, he had received a threatening letter to the newsroom, ordering him to abandon his investigations. He was given police protection and is now escorted to and from work every day. “I sometimes wonder if what I do is too risky, but we journalists owe a debt to our colleagues who have died,” says Palazzolo, referring to the eight Sicilian journalists who have been killed by the mafia for their work over the past five decades. Palazzolo is positive that the reign of Cosa Nostra, the Sicilian mafia, is far from over. “The mafia isn’t just a Sicilian problem,” he says. “It’s like a holding firm, it’s international.”

Leandro Salvia: “San Cipirello and Sicily itself are a piece of Italy and a piece of Europe.”

Leandro Salvia, 44, is the only reporter in San Cipirello, a small village about 50 km from Palermo. A soft-spoken man with a flowing salt-and-pepper haircut, Salvia writes as a freelancer for the local edition of the Giornale di Sicilia newspaper, usually from a room in his house that used to be his grandfather’s old woodworking workshop. Entertainment may be scarce in San Cipirello, a small bundle of streets atop a hill where everybody knows each other, but the place certainly doesn’t lack interesting news.

In 2018 Salvia’s investigations led to the expulsion of local council members and the dissolution of the city council itself for its collusion with mafia clans. His work angered the authorities to the point that, in July of that year, he was physically removed from the governmental meeting he was attending. This had him feeling like a pariah in his own community, a community that often doesn’t quite understand the role of a free press, he says. “I know that, geographically, I live at the borders of Europe. But San Cipirello and Sicily itself are a piece of Italy and a piece of Europe, so whenever someone breaks the law here, it’s correct that the Italian state intervenes and local reporters need to document it,” says Salvia.

Besides the intimidation he has received from local politicians and members of the public, Salvia has also faced retaliation from public sector workers who restricted his access to burial services when his father passed away. He wasn’t surprised: “When you work here you expect to be subjected to retaliation by those you write about,” he says. His house was put under moderate surveillance by police as a guarantee for his safety, and that of his wife and young children. “Often the costs are higher than the earnings, but it’s a question of civic duty. I have a responsibility to the community.”

Fabiola Foti: “Should I say that everything is fine? Write about cooking? No.”

For Fabiola Foti, editor-in-chief of the local news website L’Urlo, there are two important things in Catania: football and the festival of Saint Agatha (where a massive statue of the saint is carried through the old city during a three-day parade). Foti, 37, has worked as a reporter in the island’s second largest city, on the east coast, since she was 17. She is the daughter of a magistrate and grew up accustomed to the intimidation directed at her family. Still, she hasn’t given up on the idea that something might be done about the issue.

Over the past years, Foti has uncovered many uncomfortable truths about the way the mafia infiltrates different aspects of the city’s life. Last February, with the festivities in honour of Saint Agatha in full swing, Foti reported that a local mobster had gained access to meet with the head of the procession in defiance of the festival’s rules. A few days later, on 10 February, she found two lamb’s heads on her car’s windshield, a macabre indication that her work wasn’t welcome. This came on top of a cascade of hate messages she had been receiving online, some of which she reported to the authorities. She was briefly put under police protection.

But Foti, who is a single mother of two and sleeps for just a few hours each night, was undeterred. “The first thing I did [after finding the lamb’s heads] was to write an article about it. I called the police and then wrote about it. What else should I do, say that everything is fine? Write about cooking? No, this is what I write about,” she says. “The EU could help us,” she adds. “First off it could give financial incentives to the press, and it could also send a task force to investigate this and come up with solutions.”

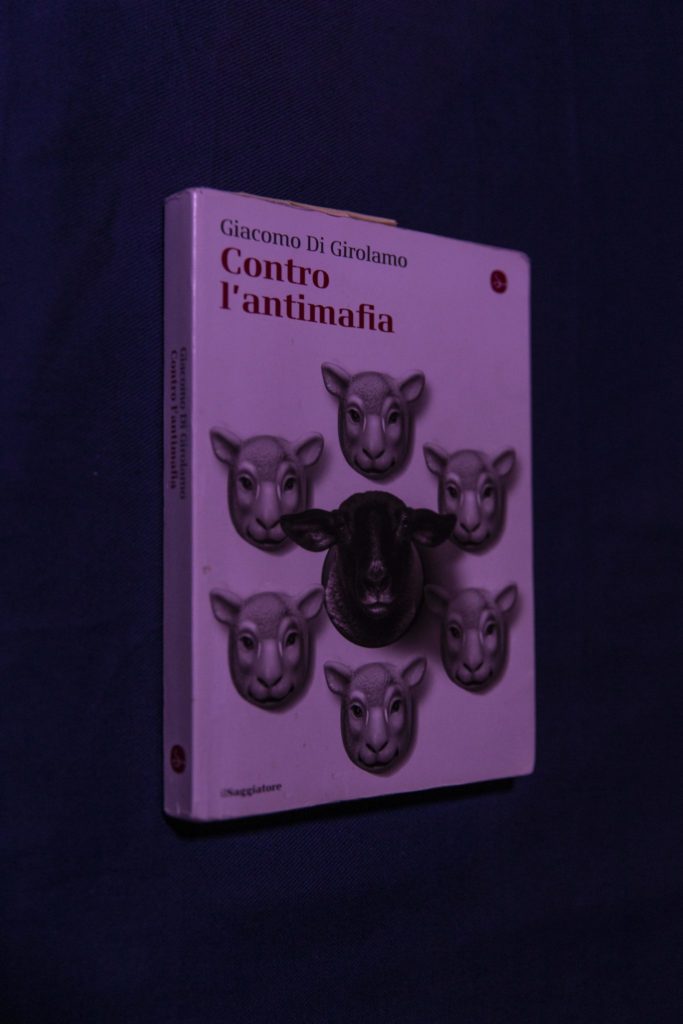

Giacomo Di Girolamo: “The choice to be a journalist at the borders of Europe is an odd one.”

Giacomo Di Girolamo, 42, is the editor-in-chief and radio host of TP24, a small news outlet covering Marsala and Trapani, two port cities on the west coast of Sicily. Throughout his career, he has received gunpowder in the mail, had criminals break into his newsroom to confront him, been intimidated on the internet by local drug lords and sued for slander countless times (this is a common occurrence in Italy and is often considered a sort of media gag.)

Nevertheless, whenever he is asked by the police whether he fears for his life, di Girolamo says he doesn’t. “A threat only works if you let it get to you,” he says, “it’s just like an insult.” Di Girolamo is eager to shake off the label of the threatened journalist and to highlight the steps that have been taken since the death of activists and reporters over a period of decades. “Thanks to the sacrifice of people like Peppino Impastato [the activist, journalist and radio host killed by Cosa Nostra in 1978] I am now free to speak my mind,” he says. “The choice to be a journalist here, at the borders of Europe, is still considered an odd one, though. You need to be ready to be attacked as a person, rarely on the content of what you write. And that’s a terrible thing.”

The problem as far as Di Girolamo is concerned isn’t personal safety so much as a lack of support and research tools that would allow journalists to maintain editorial independence in their work. He is insistent that this kind of help could come from European institutions: “There should be the chance for journalists to work well, be paid, have tools, access to databases and platforms. There is none of that for us here.”

Paolo Borrometi: “I don’t want to focus on fear.”

One afternoon in the spring of 2014, the reporter Paolo Borrometi, then aged 31, was feeding his dog in his family’s country house on the outskirts of Modica, in the south east of Sicily. Suddenly two masked men appeared, twisted Borrometi’s right arm strongly enough to break his shoulder in three parts, kicked him violently until he fell and kept kicking, all the while telling him to mind his own business, or that there would be more to come.

At the time, Borrometi was reporting on the extended network of organised crime in the province of Ragusa. From the mafia’s involvement in elections in the municipality of Scicli to the presence of illegal contractors in the cherry tomato trade, Borrometi had investigated the connections and responsibilities of various clans, publishing his findings on his news site laspia.it.

Despite the assault, which left him with a permanent disability in his shoulder, he kept working. A few months later, he and his parents barely survived an arson attack at their apartment; that’s when Borrometi was put under permanent police protection. He eventually got an offer to move to Rome to work as deputy editor-in-chief at the news agency AGI, which he accepted. In 2018, investigators in Catania foiled a plan to kill him.

Over the years, Borrometi has been a witness in 150 different trials of mobsters who have threatened him. “How can you not be afraid when you keep speaking at the hearings of people who want to kill you? But I don’t want to focus on fear. I kept going, and that’s the most important thing. My refusal to quit isn’t a personal victory, it’s a victory for public service.”

Borrometi had been corresponding with Daphne Caruana Galizia, the Maltese journalist who was killed by a bar bomb in 2017. Her death was a blow to him. “It hurts a lot,” he says. “I think the EU could do a lot more about this. We all think of the mafia as an Italian issue, it seems hard to realise that it’s spread across the whole of Europe and the world. If single states don’t protect journalists, then it’s up to Europe to do it.”

In 2018 the Italian press freedom monitoring group Ossigeno per l’Informazione reported 34 certain and 89 likely cases of intimidation against journalists in Sicily.