In Malta, women who terminate pregnancies risk up to three years in jail. Since 2018, though, when Ireland legalised abortion though a referendum, internet services have been supporting women who live on the Mediterranean island. Today, progressive and reactionary lobby groups are competing online to uphold opposing values in a changing society.

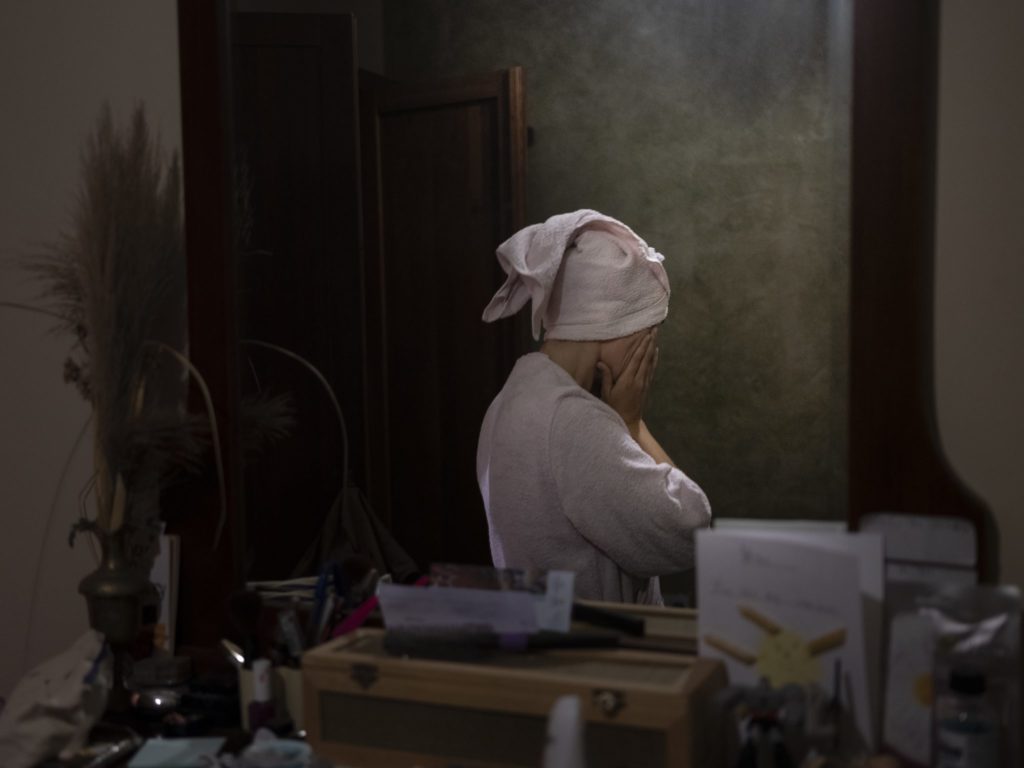

In autumn 2018, before she realised she was pregnant, Julie Borg had no idea that in Malta you could end up in jail for undergoing an abortion. “As I discovered it, I just panicked,” she recalls. Julie bought a second pregnancy test. When she read “YES” for the second time on the display she turned on her laptop in order to find out about her options.

Julie moved to Malta in the Spring of 2017, following a state-clamp down in wake of the failed coup against President Erdoğan in Turkey the previous summer. Her feelings were closely linked to these political developments, but also to her own situation at home, where she was living with her husband, Adrian. Julie’s love for Adrian faded away like air from a cheap helium balloon. She would have preferred an abrupt end to their relationship, an explosion. But she never had one. To this day Julie and Adrian still keep their separation a secret from their four-year-old son. In 2018, although Julie had left her husband and fallen in love with another man, she continued to play happy family when she and Adrian spent time with their child. Sometimes they were tempted to believe themselves and slept with each other. Both men could have been kept in the dark about the pregnancy, if only Julie could have had an abortion. “I would have preferred to keep the management of my affairs private”, says Julie. “Yet the ugliest week of my life was only about to begin.”

“We are obliged not to advise abortion.”

When Julie googled “Abortion Malta”, she found nothing of use. Instead of websites outlining services for terminating pregnancy, she was faced with dozens of pages set up by Catholic ‘pro-life’ activists. But as a single mother with a full-time job — living far away from her family, and without a stable relationship — she never questioned what the right choice was. She called in sick to her job and sat in front of her computer for a whole week. She went through online forums and informed herself about alternative abortion methods: she drank several litres of parsley brew, ate ginger and papaya seeds, and took more aspirin than her body could stand. “There was a moment, I really thought about this stereotyped image of a woman causing a self-induced abortion using a coat hanger”, she recalls. “I was ready to do anything. I had suicidal fantasies sitting at home. This one single thought was going through my mind over and over again: I need to get rid of it.” Eventually, one of Julie’s friends told her what other women in Malta do. They leave the island.

Malta’s abortion law is the most conservative in Europe. The country’s constitution enshrines Catholicism as a state religion. In other European countries, such as Poland, Andorra or Monaco, where abortion is allowed in cases where the mother’s life is in danger, or an act of rape occurred, Malta makes no exceptions whatsoever. Women who can afford fly to Germany, Belgium or England to get an abortion. Those less well-off decide to take a ferry to Sicily, reach a private clinic on the Italian island and take a trip back on the same day. According to estimates by the Green party of Malta, between 300 and 400 women leave the island each year, just to get an abortion. For the past year and a half, though, the situation has changed. Now women in Malta can order abortion pills online.

The trigger for this development was a referendum which took place on another island, some two and a half thousand kilometres away: Ireland. On 25 May 2018, 66.4% of Irish citizens agreed to remove the country’s constitutional ban on abortion. From that moment on abortion was made legal within the first twelve weeks of pregnancy or even later, in the event that the pregnant mother’s life is endangered, or in the event of fetal anomalies.

Ever since the Irish referendum, the UK-based Abortion Support Network (ASN) has been providing its services online and granting full anonymity to people living in Malta. This is a novelty on the island which has as many churches as square kilometres of land and where some 90% of residents identify themselves as Catholic. While the ‘morning-after pill’ has been available in Malta for three years, the island’s only pharmacy that is open all day long refuses to sell the pharmaceutical product on ‘moral grounds’.

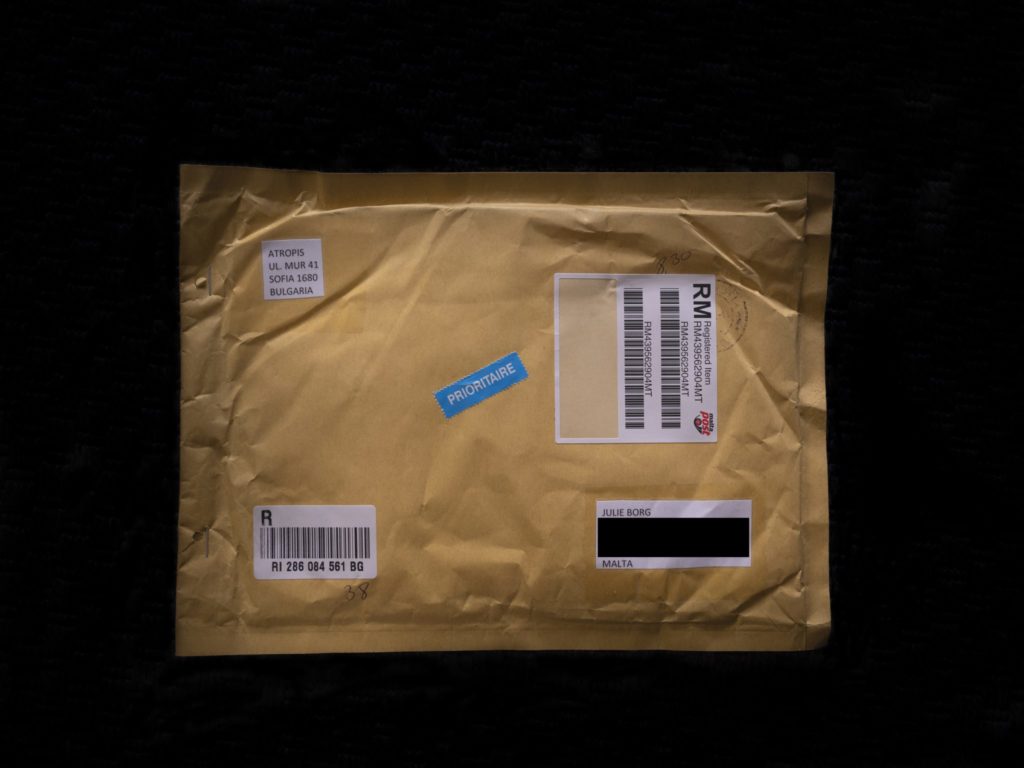

Although ASN does not sell abortion pills, the latter are marketed by Women on Web, an NGO based in the Netherlands. Yet, customs officials often withhold abortion pills. Being illegal, these pills usually come in inconspicuous padded envelopes wrapped in a silver foil and covered with stamps of all the countries they have passed through before reaching Malta. Sometimes the pills are hidden in a toy box, to disguise them in the event of border checks. They rarely come with instructions which are instead sent by email.

“It’s always dangerous to order drugs online, you never know what you’re going to get,” explains Elena Saliba, a doctor who works at the children’s department of the only state-owned public hospital in Malta. “We deal with thirteen year olds who have been raped, with risky pregnancies, including cases of congenital anomalies that could lead to the death of a fetus. Nevertheless, we are obliged not to advise abortion.” In Spring 2019, as the first ‘pro-choice’ network for women’s rights for abortion came together in Malta, the 33-year-old decided to join-up, and together with some colleagues founded the ‘Doctors for choice’ group. Shortly afterwards, Saliba’s colleagues at the hospital started collecting signatures to blackmail her. Nevertheless, the young doctor did not feel intimidated: “What I do is linked to the wellbeing of patients. Women will get an abortion anyhow, no matter if it’s legal or not. They shouldn’t risk their lives for that.”

According to Saliba, since the ASN and other networks started providing their services to Malta the number of unwanted pregnancy cases among teenagers has dropped significantly. She believes that it is mostly younger women who order a mix of Mifepristone and Misoprostol-based drugs online. But there is a concrete risk that comes with this: a pharmaceutical abortion only works up to eight weeks from conception, additionally women can suffer from heavy cramps and bleeding. There is little control involved with these online practices. And the lives of mothers are at stake. Those who terminate a pregnancy this way rarely visit a doctor afterwards for a check-up. “This isn’t just due to social stigma but also how educational programs work in schools and universities”, explains Saliba. When she studied to become a doctor, the chapter on abortions had just been bypassed. On top of that, the Catholic Church runs two schools out of three in Malta. As a student, Saliba was taught that abstinence from sex was the best form of contraception.

Catholicism is inscribed in the Constitution of Malta. The island has the strictest anti-abortion laws in the whole of Europe.

Looked at from afar, Malta can seem like a country which is all about beach parties and luxurious yachts. As a result, the social stigma that affects women rarely makes it into the headlines. In reality, though, 20% of the island’s 500,000 inhabitants come from abroad. These people bring with them a variety of different world-views which are frequently at odds with those held by a more conservative part of Maltese society which still adores crucifixes, cathedrals and pictures of the Virgin Mary. Divorce only became legal in 2011. Before then, Malta was one of just three countries in the world — together with the Vatican and the Republic of the Philippines — that did not recognise this right. Since 2014, homosexual couples living on the island have been able to enter a civil union.

The Maltese culture war

“Malta is no longer the country it once was, our society is becoming ever more progressive,” says the secretary of the civil society organisation ‘Life Network Malta’. She uses the word ‘progressive’ as if it was an insult. Her boss, Miriam Sciberra, or ‘Dr. Miriam’ as the people from the office call her, is one of the people fighting against the apparent “social decay” on the island. Sciberra — a dentist and mother of nine children — founded the ‘Life Network’ five years ago. One of the organisation’s main activities is to provide a digital hotline for pregnant women. According to Sciberra, they have managed to “save” seven babies so far.

The ‘Life Network Malta’ receives invitations to teach sex education courses in Maltese schools. They have invited anti-abortion personalities from America to talk at the island’s universities. Sciberra is also part of a pan-European network of anti-abortion activists which is sufficiently organised to the point that she has even travelled to Serbia and Romania to get training. As we sit down to talk in her office in Valletta, Sciberra doesn’t even take off her coat. She tells me, quite frankly, that there are things she simply does not discuss any more: “Abortion is murder,” period. In fact, Sciberra defines it as the “genocide of the unborn” and insists that “the trauma of abortion” is worse than rape. She also argues that, since the island is part of the EU, the “mainstream media” have conducted a “lobby campaign” in favour of abortion. Following our chat we head to a church service which marks the fifth anniversary of the network. Sciberra gets down on her knees, to pray for the unborn.

Really though, the very fact that there is such an open conflict between ‘pro-life’ and ‘pro-choice’ movements shows that a new Malta is beginning to emerge. Certainly, the situation looks very different to that which Julie Borg came to face to face with just a year and a half ago. If Julie had needed to find similar information about terminating pregnancies today she would probably have come across the ASN service. Had she googled for ‘Doctors pro-choice’, she might well have reached a website where she could have ordered abortion pills. But that autumn of 2018, when Julie was ready to do almost anything to get an abortion, these options were simply unavailable to her.

Before becoming a mother, Julie’s sex life had been going as planned. On the night of her 18th birthday, she decided to sleep with a man for the first time. After she married Adrian she decided she wanted a child. Following the separation, though, she became pregnant for a second time. In the meantime she realised that the love between her and Adrian wasn’t enough. She had met another man and another child did not fit into this new life. “I became angry at this country which was stopping me from making my own choice. I became angry at myself for doing all these things to my body. I became angry at society, which forced me to lie to everyone around me,” she explains. Eventually, though, her anger triumphed over fear.

After a week of cramps and many hours of lost sleep, Julie told both her husband and her new partner about the unwanted pregnancy. By then she was in her eighth week. Once again, she called in sick to work and told her father that she had a meeting to go to in Brussels and needed him to babysit her son. Meanwhile, Julie’s cousin booked her a medical appointment for an abortion in Turkey. Adrian bought her tickets for the flight. At the hospital he had to sign to confirm that, as Julie’s husband, he ‘approved’ the abortion. The intervention lasted about an hour and cost EUR 300. Afterwards, some friends picked Julie up and they went for a round of Raki.

Less than 48 hours later, Julie Borg was back to her usual life. To this day she’s never regretted that decision.